Pun Lun Studio

1870s

Hand-colored albumen silver print

29 x 21 cm

From the Loewentheil Collection

瑸纶影相

1870年代

手工上色蛋白印相

29 x 21 厘米

洛文希尔收藏

A highlight of the Loewentheil Collection is a large selection of works by the Pun Lun Studio, a leading Chinese photography studio. Pun Lun Studio began as a portrait painting studio. That aesthetic experience is evident in the artistic and technical mastery of its photographs, some of them finely hand-colored.

Wen Dinan, the son of the founder of Pun Lun Studio, learned the art of photography during the reign of Emperor Tongzhi. Shortly after, Pun Lun Studio offered the new art form to clients of the portrait studio. The Pun Lun Studio was one of the first Chinese commercial photography studios, continuing to produce photographs from 1864 through the turn of the twentieth century. Pun Lun Studio’s geographical reach was unparalleled with branches in Hong Kong, Foochow (Fuzhou), Saigon, and Singapore. Works from the 1860s, such as this exceptional portrait, are particularly rare because the studio’s negatives were apparently destroyed in a fire in 1876.

Meagher Mahogany Wet Plate Tailboard Camera, 10 x 10 in., with a Maugey Aine Opticiens Petzval brass len. 1860s.

The present Pun Lun Studio portrait of a woman carrying the child on her back is an artistic triumph. It captures the human tenderness and bond between the woman and the child. Accomplishing this photograph was both a technical and an interpersonal challenge. Portraits are a collaboration between the photographer and their subjects.

Cameras were not yet widespread in the 1860s, thus many people did not feel comfortable in front of the camera or the photographer. The most skilled photographers of the era instilled trust allowing their subjects to feel at ease, thereby revealing their inner dispositions. The wet plate collodion process mandated that the baby remain still for 20 seconds or longer as the negative was exposed, lest the child appear blurred. Very young children routinely appear blurred in nineteenth-century photographs. This baby’s body was restrained by the traditional Chinese baby carrier but his head was free to move. The gaze of the child’s eyes suggest a studio assistant, or relative, may be entertaining him at the side of the photographer. There is no doubt the child is very comfortable with the woman, who may be his mother or amah. The child is connected to her physically and emotionally.

Depiction of Chinese Family Culture in the Loewentheil Collection

Parents had long carried their babies on their backs in China, particularly in southern provinces. When an infant turned one month old they were allowed to leave the home with their mother for the first time. At that time the maternal grandmother traditionally presented the baby with a baby carrier. During the late Qing Dynasty, female siblings and amahs working in wealthy families would also use these traditional carriers with babies and toddlers in their care.

A baby carrier was a personal gift made of a square of dyed cloth with strips of fabric extending from the corners to provide straps. Baby carriers were often embellished with embroidered silk.

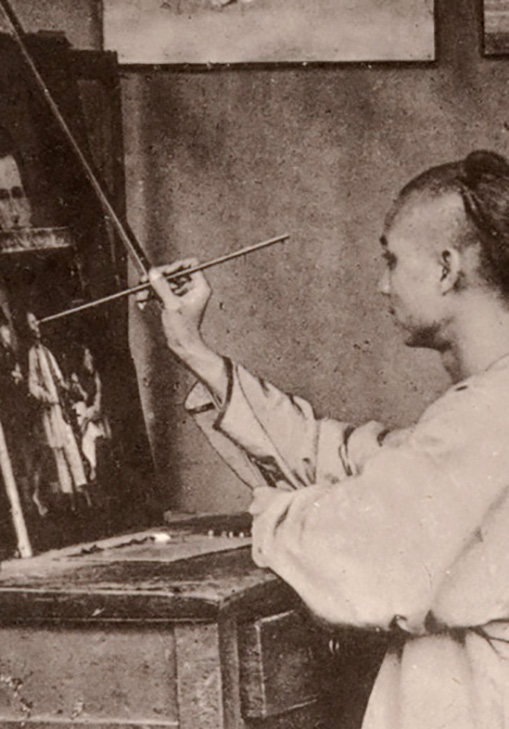

Painting a Photograph

Tinted or hand-colored photography was enormously popular among the prosperous individuals throughout the world. Portraits and genre studies served as status symbols for rising members of the professional and merchant classes. In the 1860s, Pun Lun Studio produced some of the earliest hand-colored photographs in China. Its prints depict a range of Chinese subjects.

Chinese calligraphy brush; Late Qing Dynasty

Most nineteenth-century photographs of China are monochrome albumen silver prints made from collodion glass plate negatives. In the developing process, skilled photographers like the Pun Lun Studio were able to create gradation and richness of tone with great transparency and detail in shadows. The color of the prints varied from red-violet to deep brown. Well-produced albumen silver prints were sumptuous, but colored photographs commanded even higher prices. Pun Lun Studio sold their art with and without applied color.

Chinese calligraphy pot that could be used to paint photographs; Late Qing Dynasty

In mid-nineteenth-century China, photography threatened the careers of portrait and trade painters. Chinese artisans adapted by taking jobs as photographers or colorists for established photographers. Pun Lun Studio was a portrait painting studio in Hong Kong before its owner Wen Dinan learned the art of photography in the early 1860s. Pun Lun Studio soon shifted from traditional painted portraits to fine art photography. The studio had a stable of talented artists to color the photographs it produced.

The hand-coloring process used in the Pun Lun Studio incorporated elements of traditional Chinese art. After the albumen silver prints were washed repeatedly and prepared to receive the color, the colorists would tint them with water-soluble pigments. The artists worked on wooden tables, and their supplies included brushes, inkstones, and porcelain bowls. Coloring a photograph was a precise and time-consuming process. Colorists typically produced no more than three finished prints a day.

The fine hand-tinted albumen silver prints Pun Lun Studio created in the 1860s were unprecedented in China and ushered in a new era of sumptuous photography.

John Thomson. Chinese Artists. c. 1868. From the Loewentheil Collection

蓼莪

"Thriving Thistle"

An extract from the poem 蓼莪 "Thriving Thistle" from the chapter 小雅 "Lesser Court Hymns" of 诗经 Book of Odes, the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, comprising 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th c. BCE:

以下是《诗经·小雅·蓼莪》的节选:

Tall and thriving grows the thistle.

It is wormwood instead of thistle.

Alas for my father and mother,

for all their trouble in bringing me up.

...

Without father, on whom could I rely?

Without mother, on whom could I depend?

...

My father begot me,

my mother reared me.

They raised and nurtured me.

They cultivated and educated me.

They cared about me and were reluctant to leave me.

Out and in they bore me in their arms.

Their benevolence that I would like to repay,

was as immeasurable as the heavenly sky.

蓼蓼者莪

匪莪伊蒿

哀哀父母

生我劬劳

...

无父何怙

无母何恃

...

父兮生我

母兮鞠我

拊我畜我

长我育我

顾我复我

出入腹我

欲报之德

昊天罔极

For permissions and inquiries please contact:

446 Kent Avenue PH-A Brooklyn, NY 11249 USA